(Haiku, Maui) – Several times each week, staff from the Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project (MFBRP) check mosquito traps in the rural residential areas along Maui’s north shore. Their goal is to catch as many male Southern house mosquitoes as they can.

MFBRP Coordinator Dr. Hanna Mounce explained, “Leading up to the eventual release of incompatible male mosquitoes in areas where they are spreading avian malaria and killing native forest birds, we need to monitor the success and movement of mosquitoes. We’re working in “urban” settings now and hope to duplicate our methods in the mountainous areas of Maui, where Hawaiian honeycreepers, the kiwikiu, are about to go extinct because of malaria.”

“Our best estimate for time to extinction for kiwikiu overlaps with our estimate for when incompatible male mosquitoes might be effective on a broader scale across landscapes where the birds reside,” Mounce said. Researchers hope for some cool years, perhaps giving the kiwikiu of Maui a little extra time. However, warmer years could lead to faster extinction of the tiny, yellow, forest birds.

Out in the field, Hillary Foster, a Natural Resource Data & GIS Technician with MFBRP, is joined by Kupu members Lilli Patton and Hunter Craft to check three trap sites around Haiku. As on Hawai‘i Island and Kaua‘i, where similar work is underway, they’re utilizing two different trap types. One uses fans to suck mosquitoes in and the other uses a foul-smelling liquid stew to attract them. They’re also experimenting with sound attraction and comparing catch rates to their chemical trapping results.

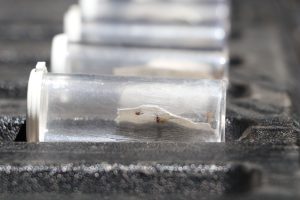

Any male mosquitoes caught by the team in fine mesh bags are aspirated into test tubes that will be sent off to labs for testing. Foster commented, “It’s hard to get into the high-elevation sites, so we’re doing our trial runs down low to figure out what the best traps and lures are for increasing our chances of catching male mosquitoes.”

For everyone working under the umbrella of the inter-agency collaborative initiative, Birds, Not Mosquitoes, the work has a sense of desperation with focused purpose. “If no one advocates for the birds and gives them voice, kiwikiu is but one species of native Hawaiian honeycreeper that will vanish in the next few years, Foster said. “Everything that is happening to our native forest birds is human caused. The birds did not ask for avian malaria and they didn’t ask for invasive ungulates that strip forests down to bare ground. I feel it’s important to help them and to right the wrongs we’ve done to them.”

The Kupu members echo what you hear universally from the people working to save honeycreeper species across the state, with Craft saying, “Protecting and saving these birds is meaningful work. They’ve been here longer than us, they evolved in Hawai‘i and are unique to this place. They have great cultural significance, and they are incredibly beautiful.”

Patton hopes to tell her grandchildren one day about the huge privilege it’s been to work on this project. “This is being part of the solution. I hope my kids and grandkids will be able to see these birds, like I have, or at least know they still exist out in nature. I want them to be able to experience the wonders I’ve been so lucky to experience.”

One set of traps is at the foot of Barbara Plunkett’s driveway in Olinda. Picked because it is a mosquito “mecca” and through her friendship with Dr. Mounce, she remarked, “It’s wonderful. I’m glad they’re doing this work and I’m glad to be a small part of the solution. Plus, the MFBRP team has shown us how to better control mosquitoes on our property.”

“We are definitely moving with this project as rapidly as we can,” Mounce said. “It is really a ticking clock on how long our birds can survive in the forested areas where they live. We can’t put all our faith in the incompatible male mosquitoes reducing populations, so we hope to bring many of the existing kiwikiu into captive care to create a viable breeding population, hoping for the day when mosquitoes are suppressed in their native habitats and they can be returned to live, wild, free, and forever.

This is the second of three DLNR releases on the Birds, Not Mosquito collaboration to control malaria-carrying mosquitoes. In November, the focus will be on work underway on Hawai‘i Island. The initiative involves top scientists, researchers, and land managers from numerous federal and state agencies, including the DLNR Division of Forestry and Wildlife.